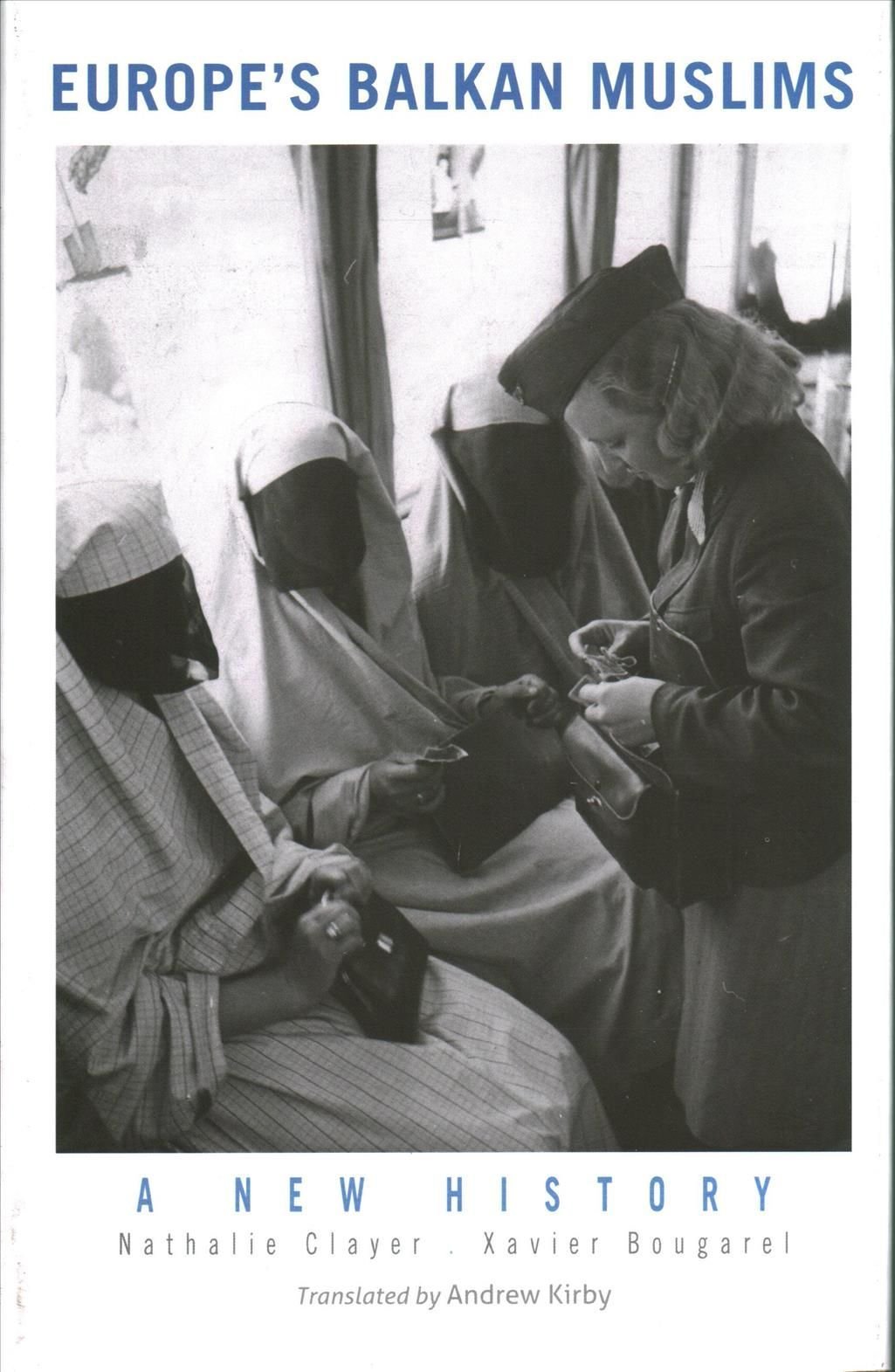

There are roughly eight million Muslims in south-east Europe, among them Albanians, Bosniaks, Turks and Roma - descendants of converts or settlers in the Ottoman period. This new history of the social, political and religious transformations that this population experienced in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries - a period marked by the collapse of the Ottoman, Austro-Hungarian and Russian Empires and by the creation of the modern Balkan states - will shed new light on the European Muslim experience. Southeast Europe’s Muslims have experienced a slow and complex crystallization of their respective national identities, which accelerated after 1945 as a result of the authoritarian modernization of communist regimes and, in the late twentieth century, ended in nationalist mobilizations that precipitated the independence of Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo during the break-up of Yugoslavia. At a religious level, these populations have remained connected to the institutions established by the Ottoman Empire, as well as to various educational, intellectual and Sufi (mystic) networks. With the fall of communism, new transnational networks appeared, especially neo-Salafist and neo- Sufi ones, although Europe’s Balkan Muslims have not escaped the wider processes of secularization.